History of St. Luke's Hospital

St. Luke's Hospital, in Manhattan, was founded by William Augustus Muhlenberg, D.D.

The Reverend William Augustus Muhlenberg, D.D. 1796-1877.

(Click photo to enlarge.)

(Click photo to enlarge.)

In the 1840s there were only two hospitals in the city: New York Hospital, sometimes called Broadway Hospital, and Bellevue Hospital. New York Hospital held 350 beds and served some indigent trauma patients, a few patients who could pay their own way, but for the most part seamen, whose expenses were paid by the government. However, only those whose cure seemed likely were admitted! Bellevue Hospital's 550 beds were devoted entirely to paupers. In her biography of Dr. Muhlenberg, Anne Ayres (see History of Nursing at SLH) writes that the conditions in the overcrowded Bellevue were worse than the basements and garretts of the impoverished patients it served.

Well aware of the dearth of health care facilities in Manhattan, Dr. Muhlenberg had long cherished a dream of opening a church hospital. On St. Luke's Day, October 18, 1846, Dr. Muhlenberg, than rector of the Church of the Holy Communionon on the corner of 6th Avenue and 20th Street in Manhattan, took the first steps to turn his dream into reality: He proposed to his congregation that half of that day's offering be set aside as the beginning of a fund to build a church hospital to care for the sick poor regardless of their religious affiliation. A little over $30 was raised, prompting a fellow clergyman to ask Dr. Muhlenberg when he expected to build his hospital. "Never, if I do not make a beginning" was the reply.

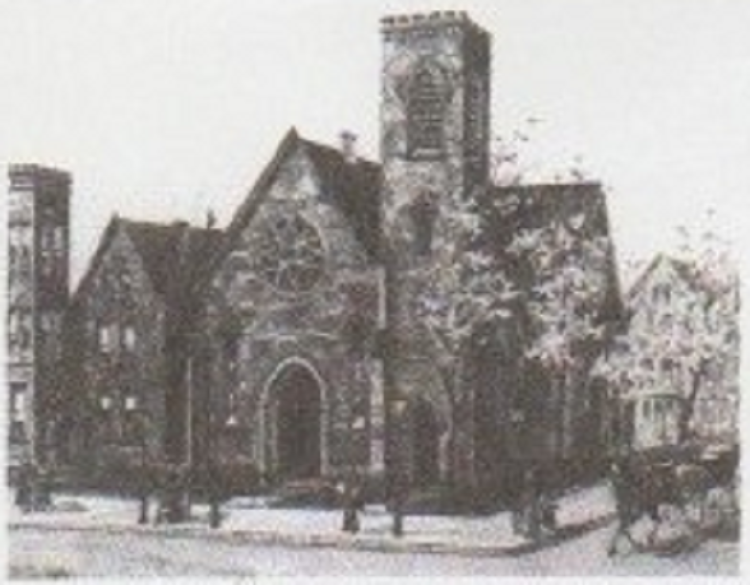

Undated print of the Church of the Holy Communion. Church designed by Richard Upjon and completed in 1844-1845.

It was the first asymmetrical rustic Gothic Revival Church

edifice in the United States and the first church in New York City to have free pews.

Dr. Muhlenberg was closely involved in the church design; he believed the Gothic style

"the true architectural expression of Christianity."

(Click photo to enlarge.)

It was the first asymmetrical rustic Gothic Revival Church edifice in the United States and the first church in New York City to have free pews.

Dr. Muhlenberg was closely involved in the church design; he believed the Gothic style "the true architectural expression of Christianity."

(Click photo to enlarge.)

His beginning was one wing and a chapel, the latter finished a year before the former. The chapel was in use almost every Sunday, establishing St. Luke's as a place of worship. On May 13, 1858, Ascension Day, the first patients were admitted to the hospital. Religion and science worked together at St. Luke's. Indeed, the motto of the hospital, which every St. Luke's graduate wears on her pin is Corpus Sanare, Animam Salvare, to heal the body, to save the soul. Dr. Muhlenberg considered the patients "guests of the Church - the Hospital a large hotel full of sick guests" with the nursing care of said guests done voluntarily by the Sisterhood of the Holy Communion (see History of Nursing at SLH). While he himself was recovering from an illness at St. Luke's, Dr. Muhlenberg said: "Thanks be to God that I am here, in this house of Mercy, this Lazarus' place which I was allowed to build for poor sufferers, and now have a home to die in. It's poetry!" Dr. Muhlenberg died in his hospital at age 81, twenty years after the first patients were admitted.

The first St. Luke's Hospital at 54th Street and Fifth Avenue.

(Click photo to enlarge.)

At the time St. Luke's was built, the property was on the northern outskirts of Manhattan, but within a few years the area was transformed into a wealthy residential district. Andrew S. Dolkart, in his book Morningside Heights A History of its Architecture and Development writes: "By 1885 the hospital building had become medically obsolete, while the presence of the austere brick hospital caring for the poor seemed incongruous."

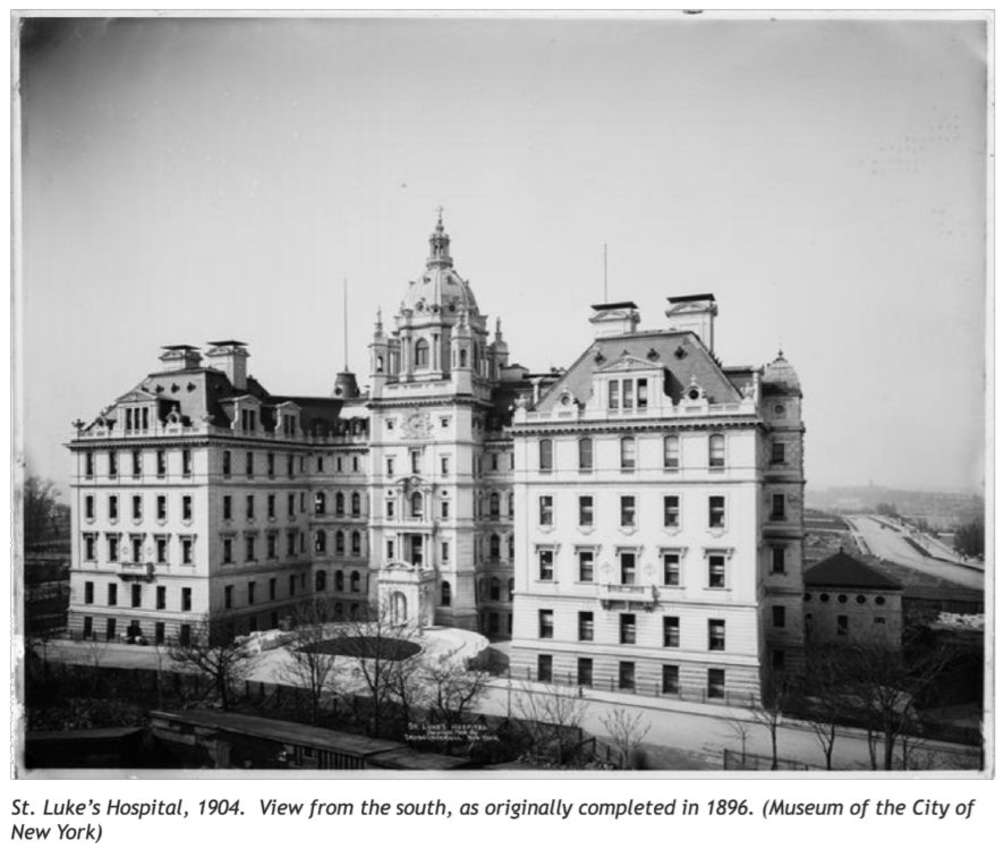

The committee appointed to search for a new location farther uptown was unsuccessful and until 1896 St. Luke's remained on land considered exceedingly valuable. According to Dolkart, an 1891 editorial in the Tribune suggested a move uptown "perhaps, in the neighborhood of the spot chosen for the new Episcopal Cathedral." In February 1892 the hospital agreed to purchase the block immediately north of the cathedral for $500,000. A design competition was held, not without controversy; ultimately Ernest Flagg, a relatively unknown young American architect was awarded the commission.

Flagg's proposed French Renaissance design, commented on in Harper's Weekly, "had the appearance of symmetrical perfectness so royal to the French Renaissance and a harmonious beauty in the rendering of detail, which two essentials all the other plans submitted in competition lacked."

The second St. Luke's Hospital at what is now 113th Street and Amsterdam Avenue.

Left to right: Norrie Pavilion, mens' wards; Muhlenberg Pavilion, administration;

Minturn Pavilion, womens' ward. (Click photo to enlarge.)

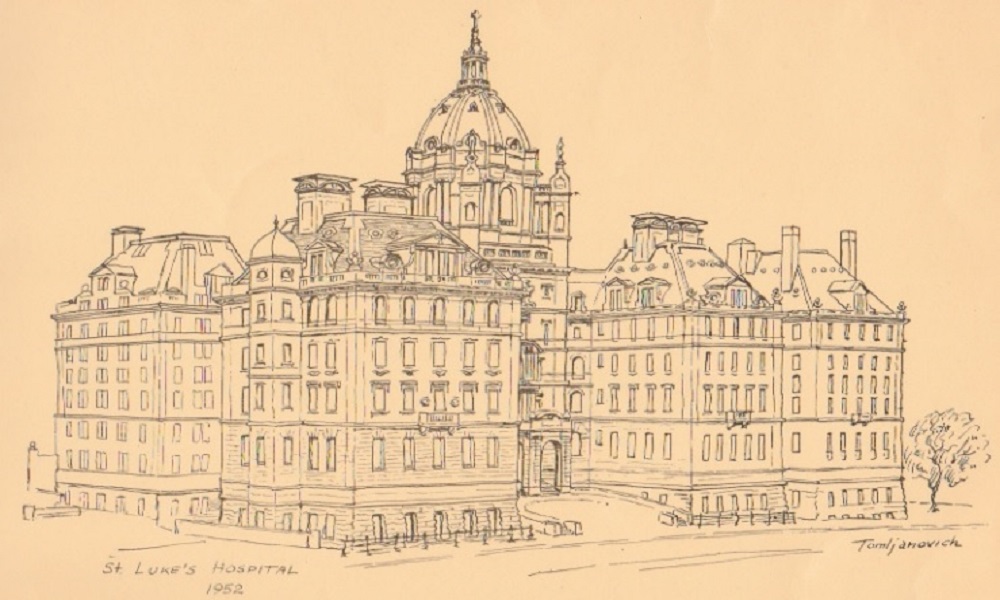

Sketch of St. Luke's Hospital, circa 1952, by Dr. Paul Tamljanovich. (Click photo to enlarge.)

When it opened in January 1896, the hospital consisted of the Muhlenberg administration building, the Norrie Pavilion, the chapel wing, Minturn and Vanderbilt pavilions, a pathology building and an ambulance stable. As funding was secured, a total of 8 Flagg-designed pavilions were constructed. Over the years, some buildings were demolished and replaced with nondescript architectural structures.

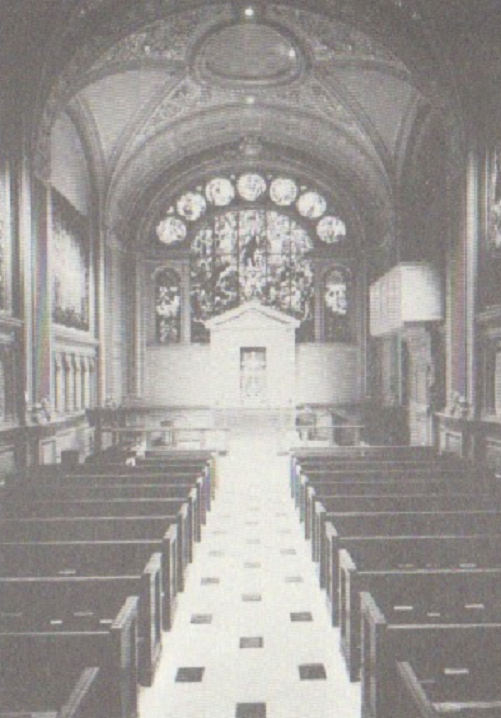

St. Luke's Hospital Chapel

Stained glass by Henry Holiday

The chapel is on an axis with the main entrance of Muhlenberg pavilion.

Attendance at Evensong was compulsory for preclinical nursing students

Monday through Friday until the late 1960s. (Click photo to enlarge.)

The hospital merged with Roosevelt Hospital in 1979 to form the St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center. In 2013 that hospital center merged with Mount Sinai, bringing together Beth Israel Medical Center and New York Eye & Ear Infirmary into the massive Mount Sinai Health System, spread from the north to the south of Manhattan. St. Luke's was renamed Mount Sinai St. Luke's. Sadly, in February 2020, with little public notice, Mount Sinai announced St. Luke's Hospital would henceforth be named Mount Sinai Morningside.

Those who knew and loved St. Luke's may find solace in knowing that Scrymser and Plant Pavilions are designated as official New York City Landmarks; the remaining original buildings are listed the National Register of Historic Places.

For a more detailed account of the architecture of St. Luke's Hospital see Dolkart, Andrew. Morningside Heights A History of its Architec ture and Development. New York:

Columbia University Press, 2001,

Chapeter Three, "Building for the Body: St. Luke's Hospital and Other Health-Related Facilities on Morningside Heights," pp. 85-102

History of St. Luke's Hospital with a Description of the New Buildings by St. Luke's Hospital and Ernest Flagg, published in 1923 has been scanned and is offered in paperback by Amazon.

A thorough history of Dr. Muhlenberg can be found in The Life and Work of William Augustus Muhlenberg by Anne Ayres, published in 1880 and available online.