History of Nursing at St. Luke's Hospital

Photograph circa 1949 showing the St. Luke's nurses' uniforms

Left to right: Graduate nurse in white with gold pin on pocket and graduate cap with black velvet band. Cap is slightly higher than the student cap;

senior student with narrow blue band around cap worn during last 6 months of training; junior student wearing bib and St. Luke's cap awarded after

preclinical period; preclinical (probie) student wearing Dutch style cap and no bib. (Click photo to enlarge.)

Nursing at St. Luke's Hospital began with Anne Ayers and the Sisters of the Holy Communion. Ayers emigrated from England in 1836, and after hearing a talk by Dr. William Augustus Muhlenberg, pastor of the Episcopal Church of the Holy Communion in Manhattan, decided to pursue a religious life. At the time, there were no established religious orders for Protestant women in the American Episcopal Church or in the Church of England; thus, Dr. Muhlenberg consecrated her a "Sister of the Holy Communion."

Sister Anne Ayres 1816-1896

(Click photo to enlarge.)

After a few women joined her in running a church school and caring for the sick poor, they were formally organized in 1852 as the Sisterhood of the Holy Communion, with Ayres as First Sister. The Sisters, who made renewable pledges of service instead of taking vows, opened an infirmary in 1853 within the church community. When St. Luke's Hospital was built in 1858, they moved there. The sisterhood and the hospital were never dissociated in Dr. Muhlenberg's mind. Without the assurance of voluntary nurses, he would not have attempted the formation of a church hospital, often saying, "No Sisters, no St. Luke's."

As the number of patients increased, applications to the sisterhood decreased. Lay women were hired to meet the nursing needs of the hospital but they functioned essentially as assistants to the sisters. It became readily apparent the system must change. Sister Anne retired in 1877; her replacement resigned because of poor health in 1888. In May of that year a graduate of the Boston City Hospital School of Nursing was hired as Head of the Nursing Department at St. Luke's. Two month later the Board of Managers of the hospital passed a resolution to establish the St. Luke's Hospital Training School for Nurses.

On July 2, 1888, six young women entered the school for a one-month probationary period. This first class of St. Luke's nurses was taught primarily on the hospital wards, although lectures, recitations and examinations on practical points of nursing were given occasionally. Students were graded on their performances; at the end of the two-year course they were awarded a diploma and a pin.

Class of 1890

The blue and white checkered dress with white bib and apron remained the student uniform until the school closed in 1974.

The St. Luke's cap was originally fashioned from that of Massachusetts General Hospital School of Nursing as seen in above photo.

(Click photo to enlarge.)

Sophie Ernst Class of 1896

By 1896 the St. Luke's cap had evolved into a taller, narrower organdy cap with distinctive side pleats;

the cap sloped downward from front to back. Eventually the uniform collar lay flatter and the

leg-of-mutton sleeves were eliminated, as were the white cuffs, although the sleeves of the dress

uniform remained long. (Click photo to enlarge.)

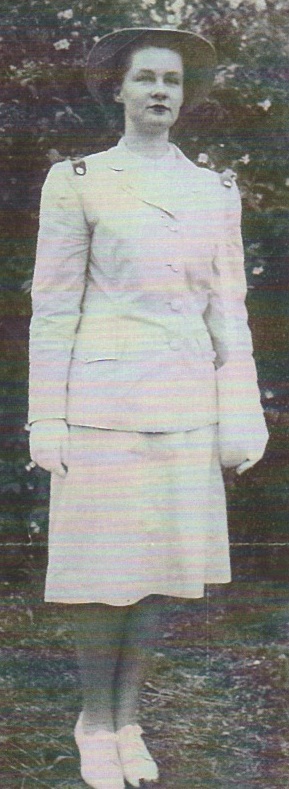

Anne Elizabeth S. Class of 1935

Many graduates from earlier classes wore the cap on the back of the head although there

were no rules as to how it should be worn. Caps were held in place by faux pearl-headed pins;

white bobby pins were also allowed. We will post more photographs of graduates wearing the

cap at different angles. (Click photo to enlarge.)

Anne Marie H. Class of 1956

The majority of graduates in the 1940s and 50s wore the cap centered on top of the head.

Several alumnae remember being told to cut soiled caps into several pieces before discarding.

Perhaps this was to preclude the cap from being copied; originally they were handmade,

but eventually were manufactured. (Click photo to enlarge.)

During the first 10 years of its existence the school added an obstetric nursing affiliation, as well as a course in the operating room for selected students; textbooks and mannequins were used for the first time. A registry for graduates who chose private duty nursing was established, and in 1896 the patients and staff moved into the new St. Luke's hospital at what is now Amsterdam Avenue and 113th Street. An alumnae association was incorporated in 1898; the first commencement was held in the hospital chapel on the evening of January 8, 1901.

The curriculum evolved in keeping with advances in the medical and nursing specialties; as course instruction increased, so, too, did the nursing faculty and the length of the training period. In 1905, in conformity to a State law enacted in 1903, the school was registered with the Regents of the University the State of New York, marking the beginning of State supervision of nursing schools in New York State.

On November 8, 1906, the Margaret J. Plant pavilion for private patients was opened for reception of patients. This was a liberating event for the students: Vanderbilt pavilion was supposedly the nurses' residence; however, during a "temporary" measure of approximately 10 years, two floors were used for private patients, an inhibiting factor for off-duty nurses. Tradition holds that on the night the patients were all moved, "the native noise-making inclinations of some 90 normal and healthy young women... were indulged in that first night of freedom to the extent of compensation for all past deprivations. And it is not recorded that anybody was disciplined as having celebrated beyond the bounds of propriety, in view of the circumstances."

Class of 1963 on stairs with ornate wrought iron railing in Vanderbilt pavilion

(Click photo to enlarge.)

The year 1915 saw the beginning of yearly appeals for a new nurses' residence. In 1917, to fill the gaps left by enlistment of nurses in war service, forty additional probationers were admitted to the training school. In order to make room for these students in Vanderbilt, graduate nurses were offered a room allowance to live outside the hospital. A canvas done by the alumnae association at the end of the war shows 197 graduates were engaged in war service in 12 countries and 48 graduates were enrolled in the St. Luke's unit of Red Cross Home Defense Nurses.

Throughout the next 10 years an entrance fee for students was instituted. Hours on duty were shortened as was the training period from three years to two and one-half, although the probationary term remained at six months. Course lectures in mental and nervous illnesses, communicable, skin, and venereal diseases were added to the curriculum; attention to the physical condition of the students improved with regular chest x-rays and immunizations against typhoid fever, smallpox, scarlet fever, and diphtheria. The fourth floor of Travers pavilion was used entirely for faculty offices and the instruction of students.

In 1928 the system of theoretical instruction was reorganized. An education director was appointed; a teaching dietician and a full-time instructor in the sciences were hired. In the hospital, a program of employing graduate nurses for "general duty" was instituted, first on the private floors and then on the wards. At the same time "ward helpers" were introduced. These women performed non-nursing duties, previously done by the nurses: brass polishing, caring for the patients' flowers, sorting and storing linen as it came from the laundry, carrying food trays, etc.

Student entrance fees were raised from $25 to $50 in the early 1930s and the training period was again extended to three years. Affiliations were added to the curriculum; a three-month course in psychiatric nursing at the Bloomingdale Hospital in White Plains, New York, (later named "The New York Hospital, Westchester Division") or at the Neurological Institute, New York City; three months in communicable disease nursing at Willard Parker Hospital in Manhattan or a two-month course with field work at the Henry Street Settlement, New York City. The later 30s saw the introduction of aptitude and intelligence tests for applicants to the school.

At last, in January 1938, the Eli White Memorial Residence was occupied by the nurses. The building was erected at a cost of $1,600,000 as a memorial to the late Mr. White from a bequest for such purpose by his daughter, Mary A. Fitzgerald. Fronting on 114th Street, the residence extended through to 115th Street and offered 355 rooms for students, graduates and faculty. A tunnel connected the residence to the hospital for use in inclement weather. (A full description of the building's facilities can be found in the first Roster in the school archives at the Foundation of the New York State Nurses in Guilderland, New York.) By the end of the 30s, health and social-physical directors were added to the staff of the school.

Entrance to the Eli White Memorial Nurses' Residence

(Click photo to enlarge.)

Over the next 10 years, the school was accredited by the National League of Nursing Education, and remained so until its closing in 1974. Chemistry, sociology and psychology were added to the curriculum, with appropriate faculty employed.

During World War II students enrolled in the Cadet Nurse Corps, a uniformed service established in 1943 within the United States Public Health Service to ensure a supply of nurses at home and abroad during the war. In return for scholarships and stipends, the student pledged to provide essential nursing services for the duration of the war, either in military or civilian life.

Throughout the war the work pace for all St. Luke's students, including cadets, was fierce. Hours on duty were long; all units were short staffed, graduate supervision was limited and the students were forced to rely on each other. At the end of the war, Helene Olandt, Director of Nursing from 1938 to 1946, commended the students and expressed thanks to them from the board of directors of the hospital and from the patients they served. In general, however, the efforts of the cadet corp nurses were largely ignored: the Public Health Service no longer needed them and the public attention they had once received for their willingness to serve was now focused on the troops returning home.

Published in Mademoiselle magazine as either a recruitment or publicity photo. In reality, arm badges were not worn

by St. Luke's cadets. Cadets and regular St. Luke's students wore exactly the same uniforms on duty. Off duty,

cadets could wear the seasonal corps uniforms. (Click photo to enlarge.)

In spite of their contributions, the cadet corps nurses are not eligible for the same types of recognition awarded other military and civilian members that served during World War II. In April 2019 several United States senators re-introduced the U. S. Cadet Nurse Corps Service Recognition Act that would grant them honorary veteran status. The bill would provide them with honorable discharges, ribbon and metal privileges and certain burial privileges. There would be no monetary rewards or health care benefits, nor would they be granted burial privileges at Arlington National Cemetery. As the legislation pends, the cadets remain the only uniformed corps members from World War II not to be recognized as veterans.

Summer Cadet Corps Uniform

Gray and white striped cotton suit with red epilauts worn with gray felt hat with large brim and red band.

Shoes were either white or black with low or medium heels and closed toes;

beige hose, a gray or

white shoulder-strap handbag and short white cotton gloves completed the outfit. (Click photo to enlarge.)

Winter top coat in gray velour with slit pockets, red epaulets and belted back worn with

black gloves and black low heeled, shoes with closed toes. (Click photo to enlarge.)

black gloves and black low heeled, shoes with closed toes. (Click photo to enlarge.)

Hundreds of nursing alumnae participated in government nursing services throughout the war. The class of 1947 published the first yearbook, Triennium, dedicated to the Second Evacuation Hospital Unit, composed of doctors and nurses recruited from St. Luke's Hospital who served in the European Theater of World War II. Student fees increased to $350 for the three-year training program; a student loan fund was developed and supported by graduates of the school.

Second Evacuation Hospital Unit

During its thirty-three months of service overseas, the unit treated and cared for 49,000 patients. In 1945 a service flag flew in the

Muhlenberg lobby with the following breakdown of personnel serving during the war: 146 medical and administrative staff with four deaths,

124 nurses with one death and 256 departmental workers. (Click photo to enlarge.)

On February 3, 1942, the alumnae association changed its name to "The Alumnae Association of the St. Luke's Hospital School of Nursing." It is unclear when the school changed its name from the "St. Luke's Hospital Training School for Nurses" to the "St. Luke's Hospital School of Nursing" but it was undoubtedly before the alumnae association name change.

In 1953, the obstetric affiliation at Women's Hospital Division of St. Luke's began. A two-week tour of duty, later a four-week tour, in the recovery room was added to the students' rotations. The system of privileges for all students was liberalized including the marriage policy. By the late 50s only one class was admitted each year; the student received her St. Luke's cap after ten months instead of after six.

Willard Parker Hospital closed and communicable disease nursing was integrated into other areas of the curriculum.

In 1959 students were no longer on the staffing roster of the hospital. By the early 60s the faculty and staff of the school had grown to 30. Following tradition, freshmen were still introduced to ward duty soon after entering the school, with their on-duty work correlated with classroom instruction. Junior year focused on obstetrics, the operating room, pediatrics and psychiatry. The senior year brought evening and night duty; advanced medical-surgical nursing; special surgery, e.g., orthopedics; urology; eye, ear, nose, and throat; the emergency room; and the outpatient department.

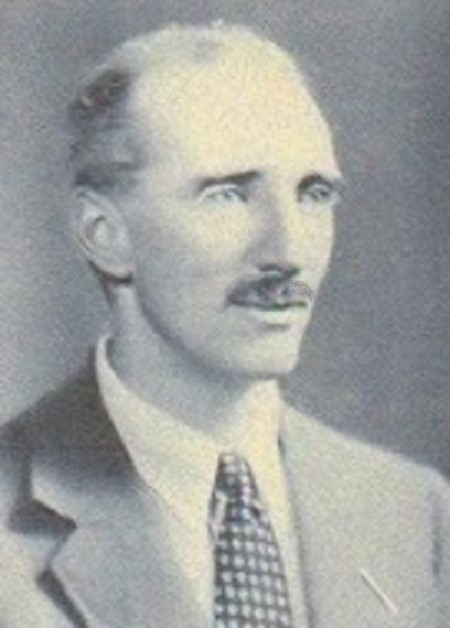

The chronology of the school from the early 1960s until its closing would be incomplete without recognition of the late Arnold Whitridge, a longtime member of the St. Luke's Hospital Board of Trustees and Chairman of the Committee on Nursing. Few nurses in the hospital family ever met him; he, however, was their true friend, tireless advocate and sometimes silent benefactor. Throughout the following history, when mention is made of updating the nurses' residence, and later undertaking a study to decide the future of the school, we credit Dr. Whitridge for securing the funding. He was instrumental in obtaining approval from the hospital trustees to establish a program whereby any graduate nurse who was employed full time at St. Luke's could receive tuition reimbursement for a specific number of credits toward her college degree. A graduate of Yale, he received his Doctor of Philosophy from Columbia University in 1925. His academic career is illustrious; during World War I he served in the British Royal Field Artillery and in the United States Army Air Corps. He was a prolific writer devoted to community service. Dr. Whitridge died in January 1989 in Salisbury, Connecticut.

Arnold Whitridge 1891-1989

(Click photo to enlarge.)

Beginning in 1960, graduation was held in September, which meant the new graduate kept her pin, graduate cap with black band and her diploma from that day forward. The decision in 1957 to admit only one class a year obviated the need to accommodate two sections of a class with a ceremony in May at which one section actually graduated and the other resumed student status for approximately three months until she completed training.

In 1964 the curriculum totaled 138 weeks; all students and faculty were granted four weeks of vacation time plus a week off at both Christmas and Easter. In two years demolition of Vanderbilt pavilion began. While not directly involved with the school of nursing for many years, faculty and students who chose not to use the connecting tunnel from the Eli White residence entered and exited the hospital complex via Vanderbilt I.

Through the late '60s the school continued to seek young women of college caliber, although more and more potential students opted for baccalaureate nursing programs rather than diploma nursing programs. The spring 1968 Bulletin asked graduates to help in recruitment by sending the registrar names and addresses of young "ladies" who might be interested in a hospital-centered program. It was evident the school must undergo change. St. Luke's, Roosevelt and Presbyterian schools participated in a study to determine the feasibility of offering college programs.

Chapel for preclinical students was no longer compulsory. Electricity in the nurses' residence was upgraded to alternating current; telephone jacks were in every room, and a student could, at her own expense, have a private line. The third floor, with classrooms, laboratories, library, and faculty offices, was air conditioned; the library was also expanded. The system of student privileges was modified to the extent she simply signed in and out. Men were allowed in students' rooms as long as the doors remained open.

Although the last capping occurred July 27, 1972, the traditions of blue banding and Friday afternoon teas continued. Students still rotated through Minturn, Plant, Scrymser, Clark, and Stuyvesant. Obstetrics and gynecology affiliation continued at Woman's Hospital, a part of the immediate St. Luke's campus since August 1965. Specialties, i.e., intensive care, hemodialysis, coronary care, emergency room, and recovery room were part of the senior rotation. The psychiatric affiliation at Westchester Division of New York Hospital, familiarly called "Blooms," was discontinued in the late '60s. Students in the Class of 1971 were the first to complete their psychiatric training at St. Luke's; the Class of 1974 affiliated at Manhattan State Hospital on Ward's Island. A great break with tradition occurred when the Class of 1970 voted to graduate in white instead of the student dress uniform, as did the three classes following.

Weekly Friday afternoon teas in the nurses' residence continued until the school closed.

(Click photo to enlarge.)

On April 4, 1972, Charles W. Davidson, Executive Director of St. Luke's Hospital, and Ruth E. Dittmar '52, Director of the St. Luke's Hospital School of Nursing, announced to the faculty and students the decision to phase out the school. It would no longer accept new students, but would maintain a quality program for those already enrolled. The decision came after seven years of deliberation, during which it became increasingly difficult for the admission's committee to recruit students who met the criteria set by the faculty. Operational costs were rising, as was tuition. Baccalaureate programs were more attractive to would-be nurses than diploma programs. The study undertaken in the mid-1960s indicated it would be best to close the St. Luke's and Roosevelt schools and change Presbyterian's degree program. Government funding was obtained; the new program would utilize clinical facilities of the three hospitals with Columbia University awarding the degree.

On announcing the closing, Mr. Davidson said: ..."Since its founding in 1888... the school of nursing has meant quality nursing. ...We believe the reputation of our school to be unmatched and our graduates have continued to bring honor to the school and to the hospital center to the present day. For all of us the decision has been a traumatic experience, but charged as we are with making difficult choices, we had no real option. The future of nursing education is in the broader educational environment of the colleges and universities. We support that view."

Graduation of the last class of St. Luke's nurses was held in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine on Friday, April 19, 1974. The ceremony, for which the 51 graduating seniors wore the student dress uniform, was witnessed by over 350 alumnae.

During its 80-plus years of existence, more than 4000 alumnae wore the St. Luke's graduate cap and pin.

Corpus Sanare, Animan Salvare